Over the past two years, the Chinese authorities have repeatedly promised to help trace any children reported to be missing in Xinjiang, to prove that they haven’t been forcibly separated from their parents. Those promises have not been met, reports John Sudworth.

The first time China made a public promise to help find Kalbinur Tursan’s children was in 2019.

“If you have people who have lost their children, you give me the names,” China’s then-ambassador to the UK, Liu Xiaoming, told the BBC in a live television interview in July that year.

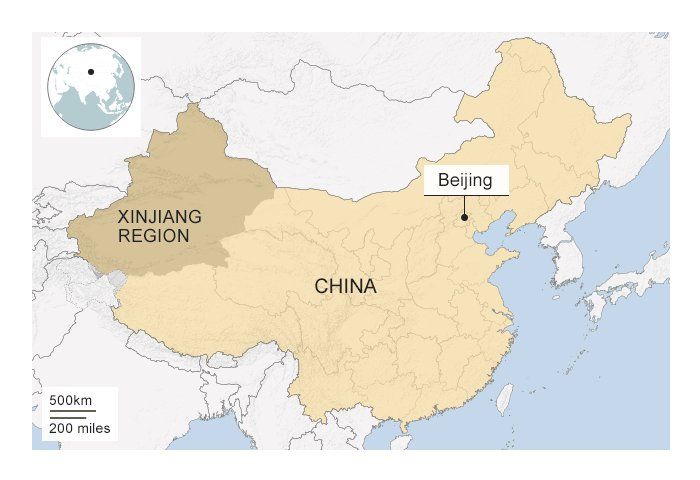

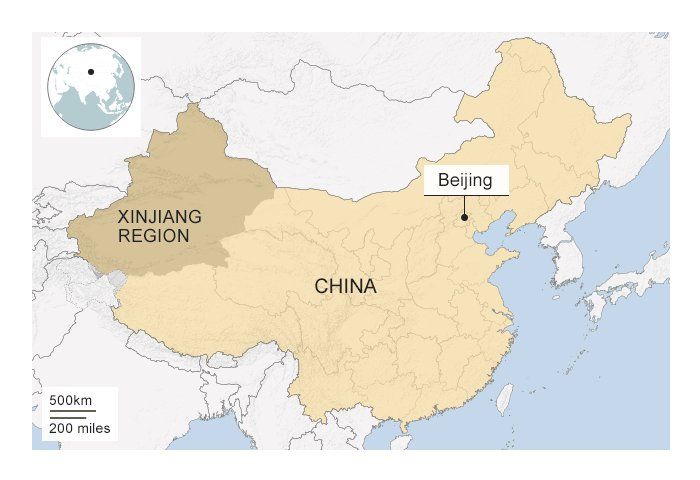

Mr Liu denied that China’s policies in its far-western region of Xinjiang could be leading to the large-scale separation of children from their parents but, he said, if we had any such evidence, he would investigate.

“We’ll try to locate them and let you know who they are, what they’re doing,” he said.https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.43.2/iframe.htmlmedia captionAmbassador Liu Xiaoming promises to help separated families

Kalbinur – a member of Xinjiang’s largest Turkic ethnic group, the Uyghurs – now lives in Turkey, working late into the night in her tiny one-room apartment sewing clothes to support what is left of her shattered family.

She arrived in 2016, eight months pregnant with her seventh child, Merziye, conceived in violation of China’s family-planning laws.

“If the Chinese authorities had known I was pregnant they would probably have forced me to abort my baby,” she told me.

“So, I prepared my body by wrapping my belly to hide the bump for two hours every day and we managed to pass the border control like that.”

Although Kalbinur had applied for passports for all of her children, China’s tough restrictions on travel for Xinjiang’s ethnic groups meant that only one – for her two-year-old son Muhammed – was granted.

With time running out, she had little choice but to leave the others behind, hoping they could follow with her husband once they’d been given their documents.

As she boarded her flight, she had no idea that she wouldn’t see them again.

Out of sight, sweeping silently across China’s vast western region, a campaign of mass-incarceration had already begun with a rapidly expanding network of what were, at first, highly secretive “re-education” camps.

A parallel network of boarding schools was also being built with the same aim; the forced-assimilation of Xinjiang’s Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other minority groups whose identity, culture and Islamic traditions were now seen as a threat by the ruling Communist Party.

One policy paper, published the year after Kalbinur’s departure, made clear that the purpose of such boarding schools was to “break the influence of the religious atmosphere” on children living at home.

A few weeks after her departure, her husband was detained and – like so many thousands of other members of the Uyghur diaspora watching their family members disappear from afar – she found herself in exile.

Almost overnight, even calling relatives became impossible because, for those still in Xinjiang, any overseas communication was seen as a potential sign of radicalisation and a key reason for being sent to a camp.

Facing almost certain detention if she returned to Xinjiang, and with her children now parentless, she’s had no contact with them at all – except for one shocking discovery.

Searching online in 2018, she came across a video of her daughter, Ayse, now two years older than when she’d last seen her, in a school more than 500 kilometres from the family home.

With her hair shaved short, she was with a group of children being led in a game by a teacher speaking not in Uyghur – her mother tongue – but in Chinese.

For Kalbinur, the video brought both relief – a tangible link to at least one of her lost children – and deep anguish, as a painful, visual reminder of the guilt and grief that have never left her.

“Knowing she was in a different city made me think it’s impossible to find my children, even if I do go back,” she told me.

“To my children, I want them to know that I didn’t abandon them, I had no choice but to leave them behind, because if I had stayed their new-born sister wouldn’t have lived.”

Kalbinur’s story is just one of a large number of similar accounts of missing children gathered by the BBC from members of Xinjiang’s Uyghur and Kazakh diasporas in Turkey and Kazakhstan.

Having first sought their permission, we sent Ambassador Liu Xiaoming the details of six of our interviewees, and attached copies of passports, Chinese ID cards and last-known addresses.

Three of the cases involved parents who had reason to believe their children were now in the care of the Chinese state.

Although his 2019 TV-appearance marked China’s first public promise to investigate, similar assurances had already been given in private a few months earlier, when the BBC was taken on a government-organised tour of the camps in Xinjiang.

The initial secrecy had given way to a new strategy, with China insisting that the camps were, in fact, vocational schools in which those under the influence of separatist or extremist ideology willingly had their thoughts “transformed”.

The Deputy Director of Xinjiang’s Publicity Department, Xu Guixiang, denied that a generation of Uyghur and Kazakh children were being effectively orphaned as whole extended families – including all adult caregivers – were detained or stranded overseas.

“If all family members have been sent to education training centres, that family must have a severe problem,” he told me.

“I’ve never seen such a case.”

But when we passed on the details of some of our cases – again, with their prior permission – the officials promised to look into it.

One of the cases – handed to the officials in Xinjiang and sent to Ambassador Liu – involved not only missing children, but 14 missing grandchildren.

Originally from the village of Bestobe in the country of Kunes in northern Xinjiang, 66-year-old Khalida Akytkankyzy – like many ethnic Kazakhs – had family ties across the border in Kazakhstan.

In 2006 she and her husband, along with their youngest son, decided to emigrate, leaving her other three sons – already married and with children of their own – in Xinjiang.

But in early 2018, the relentless machinery of mass internment caught up with them too.

Khalida received news that her three sons and their wives had all been detained “for political education”.

She tried desperately to get information, including calling the Communist Party official in her old village, but no one would tell her who was looking after her grandchildren.

By 2019, when China began claiming that the camps had been successful in combating separatism and terrorism and that almost everyone had “graduated”, for Khalida the news only got worse.

With the massive, parallel increase in Xinjiang’s formal prison population continuing unabated, her two eldest sons, Satybaldy and Orazjan, were sentenced to 22 years each, and her third son, Akhmetjan, to 10 years.

The village official told her they’d been convicted for “praying”.

If there were other reasons for their imprisonment then then the authorities have provided no details.

China’s UK embassy confirmed receipt of the letter and documents we’d addressed to Ambassador Liu but, although we sent follow-up emails in November 2019 and again in February 2020, our questions remained unanswered.

The officials in Xinjiang told us there was a “discrepancy” in the information we’d handed to them, and advised us to tell our interviewees to contact their nearest Chinese embassies instead.

In July 2020, Ambassador Liu appeared again on the same, live television programme, and was asked what had happened to his promise of a year earlier.

“I never received any names since our last show,” he told the interviewer, Andrew Marr.

“I hope that you can give me the names, we certainly will get back to you.”

He went on to suggest that his counterparts in Xinjiang would be able to facilitate such requests with ease – “they respond to us very quickly,” he added.

So, we followed up again, sending emails in August and September 2020 and in January 2021.

“Chase-up email received,” reads the latest response from an official at the embassy. “I regret no progress has been made so far.”

Nowadays, Khalida wakes early and takes a number of interconnecting buses to the Chinese consulate in the city of Almaty, just as the officials had advised us to tell her to do.

Carrying photographs of her three sons, however, she finds her daily attempts to seek answers blocked by a line of police.

“It’s not just to me,” she said in a video interview from her home.

“I’m often there with 10-15 other people and the Chinese consulate doesn’t give any information to anyone.”

In Turkey, Kalbinur is also still fighting for information about her husband, Abdurehim Rozi, and her five missing children, Abduhalik, Subinur, Abdulsalam, Ayse and Abdullah.

She recently took part in a 400km walk from Istanbul to Ankara with other Uyghur mothers, in a bid to break the silence of the Chinese authorities about their relatives.

Her campaigning has at least prompted a limited response, in a press conference – chaired by Xinjiang’s deputy propaganda chief, Xu Guixiang – denying that her daughter is in a boarding school and insisting instead that the children are being looked after by a relative.

But Kalbinur is still unable to contact them and so China’s claims are impossible to verify.

“I want the authorities to let me see my children,” she told me over a video call as she took a break from her protest walk at the side of a busy highway.

“In this information age, why can’t I contact my children?”

One of the cases we sent to Ambassador Liu did not involve missing children, but a missing mother instead.

In 2017, Xiamuinuer Pida, a 68-year old retired engineer with a long service record at a Chinese state-run company, was sent to a camp, where she was interned for 18 months before being released.

Her daughter, Reyila Abulaiti, who has lived in the UK since 2002, says the authorities are still refusing to grant her mother a passport, keeping her – like many other former camp inmates – under close surveillance in her home.

During our 2019 visit to Xinjiang, Chinese officials insisted that she was entirely free but simply suffering from ill health, with one of them telling us that many elderly Uyghurs suffer dietary problems – “too much meat and milk,” he said.

It was a suggestion that infuriated and saddened Reyila, who told me that her mother had, in fact, lost 15kg (33 pounds) in weight as a result of the harsh conditions during her incarceration.

“They’re trying to hide what they are doing,” she replied, when asked about the authorities’ failure to explain why Xiamuinuer had been sent for re-education.

“She’s a well-educated, retired woman, she doesn’t need vocational courses. She’s been in a camp and they don’t want my mum to speak out.”

Earlier this year, Liu Xiaoming completed his tenure as Chinese ambassador to the UK, with an online farewell to British politicians and dignitaries and with his promise still unmet by the Chinese authorities.

Meanwhile, I’ve been forced to leave China as a result of the increasing pressure from the authorities over my journalism and, in particular, a growing number of threats to sue me over my reporting on Xinjiang.

Some of those threats have come directly from Xu Guixiang, the official I’d interviewed two years previously in Xinjiang.

The BBC had produced “fake news” and violated professional ethics, he told China’s Communist Party-run media.

Yet despite the continued insistence of Chinese officials that – if we provided names – a quick search would easily disprove that families were being forcibly divided, they have offered only silence.

In addition to those already mentioned, we’re still waiting to learn the whereabouts of a number of other children, including those of Yasin Zunun, who suspects that Muslima, Fatima, Parhat, Nurbiya and Asma are in a boarding school.

Merbet Maripet has heard nothing from her four children, Abdurahman, Muhammad, Adila and Mardan since 2017, and also believes they’re now in the care of the state.

We asked the Chinese Foreign Ministry why no branch of government has been able to deliver on the clear promises to provide information about the missing individuals.

No response was received before this report was published.

Producer: Kathy Long