In addition to the heavy restrictions it places on foreign journalists trying to report the truth about its far western region of Xinjiang, China has a new tactic: labelling independent coverage as “fake news”.

At night, while travelling for hours along Xinjiang’s desert highways, the unmarked cars that had been following us from the moment we arrived would tailgate us at speed, driving dangerously close with their headlights on full beam.

Their occupants – who never identified themselves – forced us to leave one city by chasing us out of restaurants and shops, ordering the owners not to serve us.

The report we produced, despite these difficulties, contained new evidence – much of it based on China’s own policy documents – that thousands of Uighurs and other minorities are being forced to pick cotton in a region responsible for a fifth of the world’s crop.

But now China’s Communist Party-run media have produced their own report about our reporting, accusing the BBC of exaggerating these efforts by the authorities to obstruct our team and calling it “fake news”.

The video, made by the China Daily – an English-language newspaper – has been posted on both Chinese social media sites, as well as international platforms banned in China.

Hannah Bailey, who specialises in China’s use of state-sponsored digital disinformation at the Oxford Internet Institute, suggests that such a fiercely critical attack in English, but with Chinese subtitles, makes it unusual.

“It has clearly been produced with both international and domestic users in mind,” she told me, “which is somewhat of a departure from previous strategies.

“Previous content produced for mainland audiences has been more critical of Western countries, and more vocally nationalistic, whereas content produced for international audiences has struck a more conciliatory tone.”

The China Daily report focuses on an altercation outside the front gate of a textile factory in the city of Kuqa, where the BBC team was surrounded by a group of managers and local officials.

The allegations it contains, based on body camera recordings provided by the police who arrived at the scene, are easily dismissed. A polite exchange between our team and a police officer is used to suggest that the BBC exaggerated the role of the authorities in preventing us from reporting.

But the China Daily chooses not to mention that some of our footage was forcibly deleted and we were made to accompany the same police officer to another location so she could review the remaining pictures. And it provides no explanation of the wider context, nor gives the BBC any right of reply.

Over a period of less than 72 hours in Xinjiang we were followed constantly and, on five separate occasions, approached by people who attempted to stop us from filming in public, sometimes violently.

In at least two instances, we were accused of breaching the privacy of these individuals on the basis that their attempts to stop us had led them to walk in front of our camera.

The uniformed police officers attending these “incidents” twice deleted our footage and, on another occasion, we were briefly held by local officials who claimed we’d infringed a farmer’s rights by filming a field.

China’s propaganda efforts may be a sign of just how damaging it believes the coverage of Xinjiang has been to its international reputation.

But attempting to attack the – usually censored – Western media at home carries some risk, in that it can reveal glimpses of stories that would otherwise remain out of the public domain.

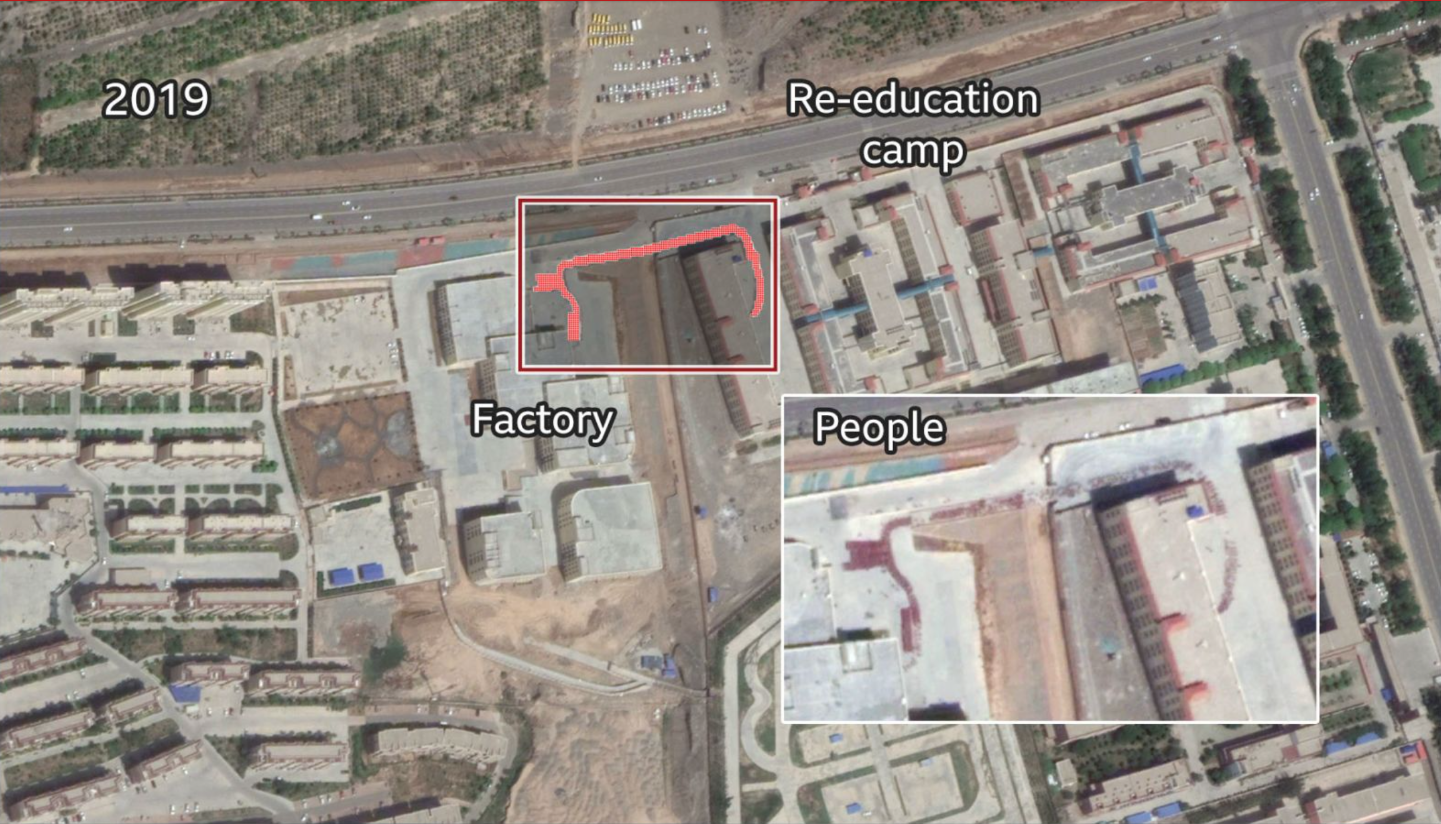

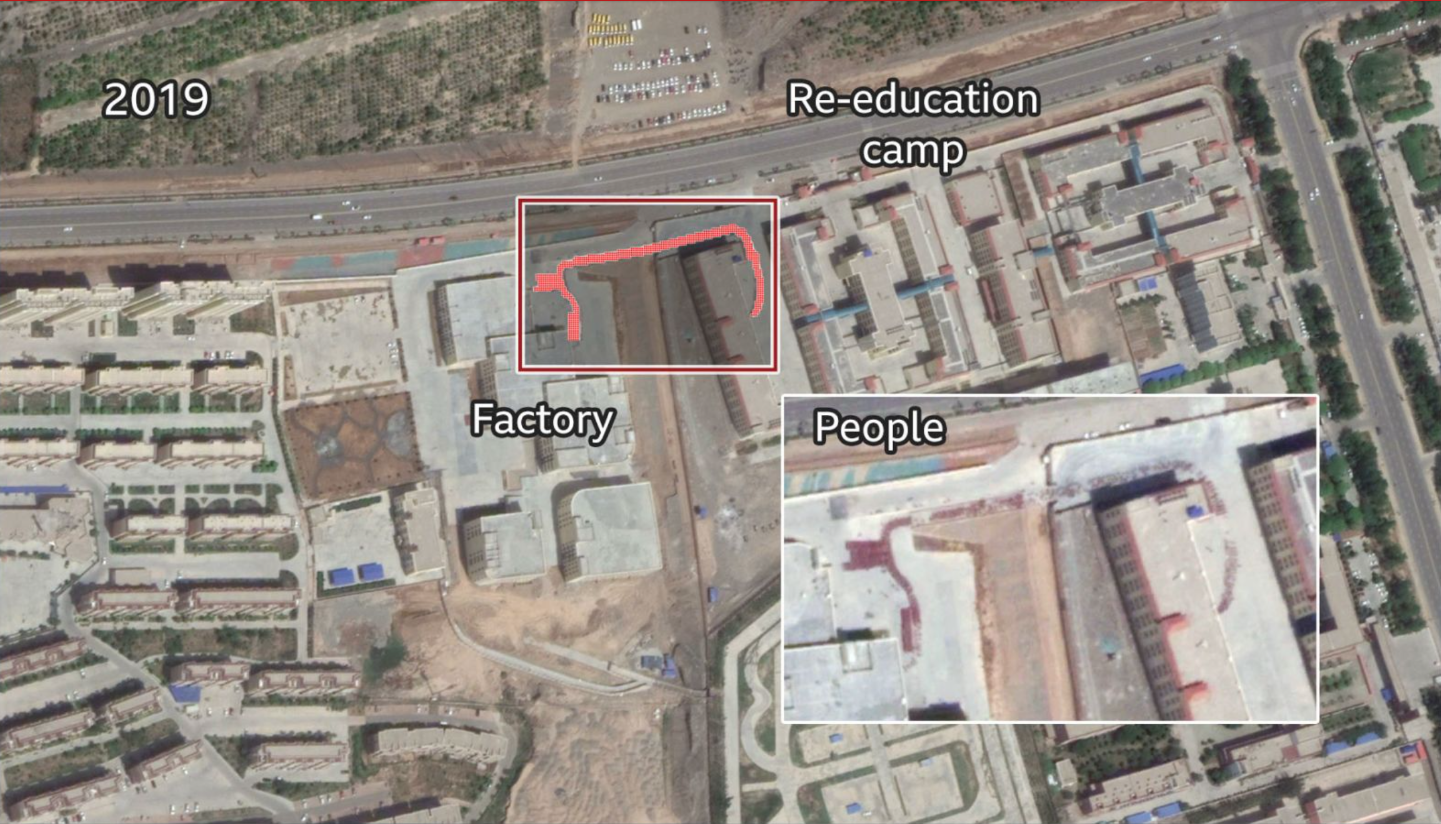

A satellite photo, dated May 2019, shows a large group of people being moved between the Kuqa textile factory and a re-education camp located next door, complete with a watchtower and internal security walls.

The China Daily, which refers to the camp by the official terminology as a “Vocational Training Centre” suggests our attempt to film was pointless because, they say, it closed in October 2019.

If true, this simply proves that the camp was operational when the image was taken – and confirms it to be compelling grounds for further investigation.

Now Chinese and Western audiences alike can ponder who the people in the photograph were, why they were being moved between the camp and the factory and whether any work they did there was likely to be fully voluntary.

In an interview with one of the uniformed police officers who provided the body camera recordings, the China Daily video inadvertently provides corroboration of just how well-planned and multi-layered the control of journalists in Xinjiang really is.

The officer confirms that, shortly after our arrival in Kuqa, she summoned us to a meeting in our hotel lobby to issue a warning about “our rights and restrictions”.

In fact, hotel staff told us we were forbidden to leave the hotel until after this meeting had taken place.

It was also attended by two propaganda officials who were assigned to accompany us for the rest of our time in Kuqa – adding one more car to the long line that followed us wherever we went.

Far from being fake news, our evidence, along with the post-publication propaganda designed to undermine it, is proof of a co-ordinated effort to control the narrative, extending from the shadowy minders in unmarked cars, all the way up to the national government.

Upon our return to Beijing we were summoned to a meeting with officials who insisted that we should have sought permission from the owners of the factory before filming it.

We pointed out that China’s own media regulations do not prohibit the filming of a building from a public road.

China is increasingly using the accreditation process for foreign journalists as a tool of control, issuing shortened visas and threats of non-renewal for those whose coverage it disapproves of.

Following publication, I was given another shortened visa with the authorities making clear that it was as a result of my reporting on Xinjiang.

The China Daily also accuses the BBC of using a hidden camera – we didn’t.

And it misrepresents the recording from the police body cameras by suggesting a comment made by BBC producer Kathy Long outside the factory, that we wouldn’t use images of one man, were instead made in regard to someone else.

Presuming they’re in possession of the full recording it is hard to understand how this mistake could be made.

Hannah Bailey from the Oxford Internet Institute says, like China’s domestic propaganda, its international push-back may be becoming “increasingly critical and defensive”.

“China has previously demonstrated its use of a variety of tools to manipulate international and domestic discourse, from Twitter bots to state-controlled international media outlets to the vocal so-called “Wolf Warrior” diplomats,” she told me.

“Attempts to discredit foreign media are also a part of this toolkit.”

We offered the China Daily the opportunity to comment on the errors in its reporting.

In a reply, which failed to address our specific questions, it said that having visited Xinjiang and conducted interviews it has concluded that “there is no forced labour in Xinjiang”.

Its propaganda video ends with a worker in the Kuqa textile factory being asked why she’s there – a question that comes, she will know full well, from reporters under the direct control of the Chinese Communist Party.

“I chose to work here,” she tells them.