The whole world seems to be talking about the climate crisis, thanks to months of wild weather and new science showing that we need to act quicker than we previously thought to avoid the worst consequences.

As global leaders meet in the Egyptian resort city of Sharm el-Sheikh for annual climate talks, they’ll be using a lot of technical lingo. But the terminology isn’t particularly helpful and can be daunting.

Even the name of the summit – COP27 – sounds more like a bad police drama than a climate event. (First pointer: COP is short for Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Climate Change. It convenes global leaders, scientists and negotiators on climate, and usually takes place annually. The “27” means this will be the 27th meeting.)

Here are other terms to know to keep up with the talks, understand what’s at stake and, most importantly, sound smart around the dinner table.

1.5 degrees

A key goal of recent COPs, and of the fight against climate change in general, is “keeping 1.5 alive,” which refers to a target to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels. It’s a target that some fossil fuel-producing countries have resisted, and scientists have warned of significantly worse impacts if this threshold is breached.

The countries that signed the Paris Agreement in 2015 agreed to limit the increase in global temperatures to well below 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, but preferably to 1.5 degrees.

However, a UN report released in October found that current pledges and plans to reduce emissions will not get us anywhere close to staying under this threshold. The latest global pledges, including some made in the past year since COP26, will reduce planet-warming emissions in 2030 by about 5% – but a 45% reduction is what’s needed to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees.

Under current climate policies, the report said that the world will reach 2.8 degrees by 2100.

The UNs’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said in its latest state-of-the-science report that the world has already warmed by 1.1 degrees above than pre-industrial levels, and is now hurtling fast toward 1.5 degrees.

Renewable energy

Scientists have showed that the world needs to transition away from fossil fuel and toward renewable energy to keep global temperatures from rising more.

Renewable energy comes from sources that can’t run out, and the term is typically used to describe energy sources that have no or very low planet-warming emissions.

Although they were created in natural processes, fossil fuels like coal, gas and oil are limited in that they take millions of years to form deep underground.

Common examples of renewable energy include wind, solar and geothermal.

Wind turbines harnesses the atmosphere’s natural kinetic energy and converts it into electricity. The planet’s potential to generate wind energy is vast, particularly in very windy locations offshore.

Solar power is generated by converting sunlight – our most abundant natural energy resource – into electricity through photovoltaic panels.

Geothermal energy involves using the Earth’s heat that’s way below ground level to heat homes, water or generate electricity.

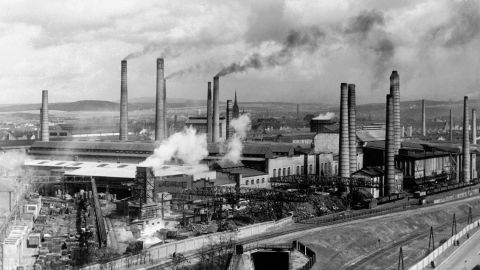

Pre-industrial levels

This usually refers to average concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere before the Industrial Revolution, which started in the late 18th century.

CO2 levels are estimated to have been around 280 parts per million at that time. By 2021, that concentration had risen to 415.7 parts per million, according to the latest Greenhouse Gas Bulletin released by the World Meteorological Organization ahead of COP27.

Scientists also talk about pre-industrial levels for average temperatures, using the period 1850-1900 to determine how hot or cold the Earth was before humans began emitting greenhouse gases in large volumes.

Net zero emissions

Net zero emissions can be achieved by removing as much greenhouse gas from the atmosphere as what’s emitted, so the net amount added is zero.

To do this, countries and companies will need to rely on natural methods – like planting trees or restoring grasslands – to soak up carbon dioxide, the most abundant greenhouse gas we emit, or use technology to capture the gas as its emitted so it doesn’t enter the atmosphere.

Dozens of countries have already pledged to achieve net zero by mid-century and there is huge pressure on the remaining countries to do so.

Negative emissions

To save the world from the worst effects of climate change, scientists say it’s probably not enough to reach net zero – we’ve got to hit negative emissions.

Negative emissions is the situation where the amount of greenhouse gas removed from the atmosphere is actually more than the amount humans emit. This would require a significant energy overhaul as countries would need to ramp up renewable energy rapidly and invest heavily in technology to suck emissions out of the atmosphere.

Carbon sinks

This is a reservoir that absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and locks it away.

Natural sinks like trees and other vegetation remove CO2 from the atmosphere through photosynthesis – plants use the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to grow. The ocean is also a major carbon sink because of phytoplankton which, as a plant, also absorbs carbon dioxide.

Scientists say preservation and expansion of natural sinks – like the Amazon Rainforest – are crucial to reducing emissions.

There are also artificial carbon sinks that can store carbon and keep it out of the atmosphere. More on that below.

Carbon capture and storage

Technology to remove and contain carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is known as carbon capture and storage. Carbon is usually captured at source – directly from coal, oil or gas as it burns – but new technology is being developed to literally suck carbon from the ambient air.

In both cases, the carbon can be stored, usually buried in reservoirs underground or below the floor of the sea, in what are known as artificial carbon sinks. Some scientists warn that it could be risky to inject so much carbon underground, and this process isn’t currently used on a large scale. The Global CCS Institute says just 27 commercial facilities are fully operating worldwide, while more than 100 others are in development.

But other experts say this technology is necessary to put a real dent in our emissions.

There are many ways to capture and store carbon. Here are some of them:

- Carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS) is a process in which CO2 produced by heavy industry or power plants is collected directly at the point of emission, compressed and transported for storage in deep geological formations.

- Carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) refers to the collection of CO2 from industrial sources, which is then used to create products or services, such as manufacturing fertilizer or in the food and beverage industry. (Fun fact: This CO2 can be pumped into your beer to make it fizzy.)

- Direct air capture and storage (DACS, DAC or DACC) is a chemical process which removes CO2 directly from the air for storage. There were 15 direct air capture plants operating worldwide, according to a June 2020 International Energy Agency (IEA) report.

NDCs

Nationally Determined Contributions – or NDCs – is a term used by the UN for each country’s individual national plan to slash greenhouse gas emissions.

In the 2015 Paris Agreement, which nearly the whole world signed on to, countries were given the freedom to determine themselves how they would go about meeting the agreement’s key targets to slow global warming.

NDCs are supposed to be updated every five years and submitted to the UN, the idea being that each country’s ambition will grow over time.

Climate finance

More than 10 years ago at COP16 in Cancún, Mexico, the developed world agreed to transfer money to developing countries to help them limit or reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the climate crisis. They set up the Green Climate Fund (GCF) to facilitate some of this transfer, but countries and donors can send money through any means they like.

The money was supposed to build up and reach $100 billion annually by 2020, and that commitment was reaffirmed in the Paris Agreement. This money is often referred to broadly as “climate finance.”

But the 2020 target was missed, and filling the gap is high on the agenda for the talks in Egypt this year.

Developing nations, particularly those in the Global South, which are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, argue that industrialized nations are historically more responsible for climate change and must do more to fund changes to help developing nations adapt and transition their economies to renewable energy.

US President Joe Biden pledged to double the US’ existing contribution plans, including money for the Green Climate Fund, in a speech at the UN General Assembly in 2021.

Whether Biden can marshal that much funding is still unclear; Congress has not yet finished its appropriations process for the coming fiscal year, and it remains to be seen whether the amount of money the president wants for climate finance can pass by the end of the year.

Adaptation

Adaptation refers to the way humans can change their lives and infrastructure to better cope with the impacts of climate change.

These changes might include building early warning systems for floods, or barriers to defend against rising sea level, for example.

In some places where rainfall is decreasing, planting drought-resistant varieties of crops can help ensure communities have enough food to eat.

Mitigation

Put simply, this refers to how humans can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, or remove them from the atmosphere, to ease the consequences of climate change.

Examples include using fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas more efficiently for industrial processes, switching from coal and gas to renewable energy sources such as wind or solar power for electricity, choosing public transport to commute over private vehicles that run on gasoline, and expanding forests and other means of absorbing carbon.

Unabated coal

You might hear leaders talking about ending “unabated” coal use. Unabated coal refers to coal burned in power stations where no action – or “abatement” – is taken to reduce the greenhouse gases emitted by its use.

In short, this creates a loophole for to keep using coal in a net-zero world, if the greenhouse gas it emits is captured.

Very few coal plants in the world, however, are using abatement technologies, and transitioning to renewables is often more economically feasible in the long term than employing them.

In its 2021 report “Net Zero by 2050,” the International Energy Agency states that a “rapid shift” will be needed away from fossil fuels to achieve the goal, requiring steps such as “phasing out all unabated coal and oil power plants by 2040.”

EVs

That’s electric vehicles to you and me.

As electricity generated by renewables, like wind and solar, becomes more available, people are expected to start buying electric vehicles in greater numbers, especially as they become more affordable. That will mean fewer cars powered by oil on the roads, which will be a major topic at COP27 given the global energy crunch amidst Russia’s war in Ukraine.

There may also be references to PHEVs – those are plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, which are mostly powered by a battery charged from an electrical source but also have a hybrid internal combustion engine to allow travel over longer distances.

Just transition

This refers to the idea that the drastic changes needed to combat climate change should be fair to everyone.

As environmental campaign group Greenpeace says: “Put simply, a just transition is about moving to an environmentally sustainable economy (that’s the ‘transition’ part) without leaving workers in polluting industries behind. It aims to support good quality jobs and decent livelihoods when polluting industries decline and others expand, creating a fairer and more equal society – that’s what makes it ‘just.’”

Biodiversity

Biodiversity refers to all the Earth’s living systems, on land and in the sea.

The UN’s Global Biodiversity Outlook report published just over two years ago warned that the accelerating climate crisis was worsening the outlook for biodiversity – that can mean all the trees, plants and animals in a forest, or all the fish and coral in a reef. “Biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented rate, and the pressures driving this decline are intensifying,” it said.

Challenges include habitat loss and degradation, mass extinction of species, declining wetlands, and pollution by plastic and pesticides.

Last year, the G7 countries – the seven largest advanced economies – agreed to conserve 30% of land and sea in their nations to protect biodiversity, a pledge they reaffirmed in 2022.

CNN’s Brandon Miller contributed to this report.