There’s a scene in the Downton Abbey pilot in which the landed Crawley family’s sumptuous evening meal is marred by a dinner guest’s shocking disclosure that he has a real job. When the guest explains that he has time for other pursuits at the weekend, Maggie Smith’s wealthy dowager inquires with a hint of alarm: “What is a weekend?”

It’s a question those of us with non-essential jobs have had plenty of time to ask in recent weeks as schools, offices and public spaces of all kinds have closed to slow the spread of coronavirus. Confined to our homes and stripped of our daily routines, many in self-isolation have found that time has become a strange and amorphous thing that can’t be defined by a calendar.

If you’re still in pajamas and both the TV and your work laptop are on, does it matter what time it is? If you’re still ping-ponging between work that needs finishing and kids who need snacks, does it matter what day of the week it is? What is a weekend, really, and is it even possible to have one in a quarantined world?

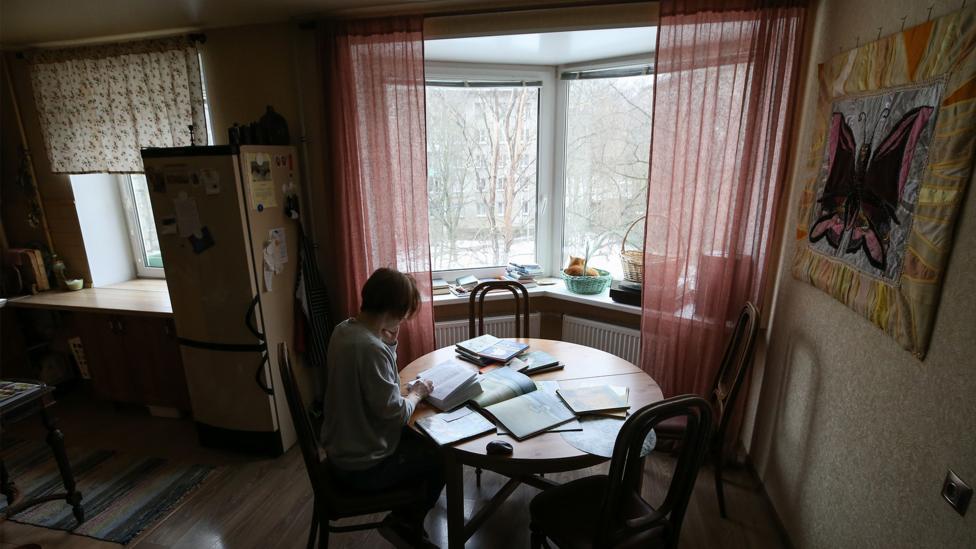

Veronika Makarova reads fairy tales to children on the phone, working from her apartment during the Covid-19 pandemic (Credit: Getty Images)

Something to look forward to

“One of the challenges of the current crisis is that many of our schedules are completely in disarray,” says Laurie Santos, a psychology professor at Yale University who teaches the popular course The Science of Well-Being. “Humans are creatures of habit, so having a regular schedule for when we work and when we engage in leisure can help us reduce uncertainty, especially in this already uncertain time.”

In normal times, that regular schedule is dictated for us by external forces: school schedules and train times, work meetings and appointments. Without those, people around the world have had to craft their own creative ways to distinguish downtime from regular time.

Chaney Kourouniotis is a Seattle-based marketing director for the travel company Rick Steves Europe. Though she’s now working at home, she’s continued to set an alarm so that she can rise and be at her desk at her regular time. Sleeping in is a pleasure she reserves for weekends.

For those with kids at home, leisurely mornings on any day are often out of the question. Emily Seftel works in administration for an international organisation in Paris, her husband works in tech, and they’re juggling both jobs at home with care and schooling for their six-year-old son. To ensure they look forward to their weekends, they’ve instituted a rule: each weekend day, each parent gets three hours to themselves alone, in whatever space they can find in the apartment.

“The other members of the family pretend that parent isn’t there,” Seftel says. “We alternate mornings and afternoons. This last weekend I got Saturday morning and Sunday afternoon off to read on the balcony in the sun, lock myself in the bedroom with Netflix, to do whatever I wanted.”

Man-made cycle

Why do weekends matter? Unlike the 24-hour daily rotation of the Earth or its year-long journey around the Sun, the seven-day week is a purely social construct, as the journalist Katrina Onstad notes in her book The Weekend Effect: The Life-Changing Benefits of Taking Time Off and Challenging the Cult of Overwork.

In fact, the two-day weekend was in part born from another economic crisis, Onstad says. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, many industries that had not yet adopted the 40-hour workweek cut employee schedules back to five days a week, so that fewer working hours could be distributed among more people. By 1938, the 40-hour workweek was enshrined into law with the Fair Labor Standards Act.

It’s possible that this current crisis will lead to long-standing changes as well.

“Even before the coronavirus pandemic, the traditional working week was changing,” says University of Portsmouth history professor Brad Beaven, citing the rise in remote working, self-employment and gig economy jobs. “Strangely enough, self-isolation has … enabled the worker to determine their own cycle of productivity, their breaks and own work routine.”

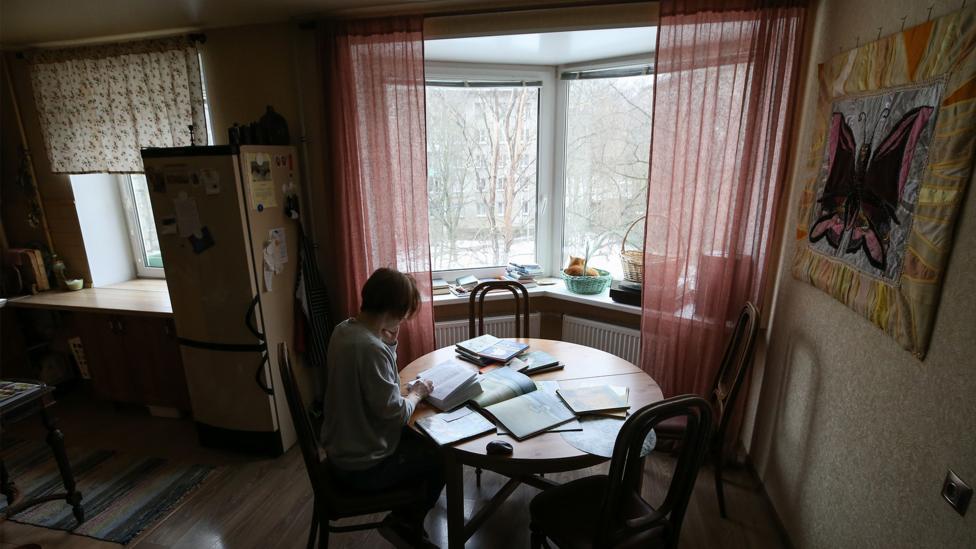

A young student attends an online class during the quarantine in Milan, Italy (Credit: Getty Images)

‘Bring some normalcy back’

How society will change its habits in response to this crisis remains to be seen. For individuals, though, establishing some kind of structure to the day and week is a critical component to surviving the uncertainty and strain of the coming weeks.

“If you don’t want to get things done, it doesn’t matter” if you have a routine, says Nir Eyal, a productivity consultant and author of Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life. “If you need to get things done, it’s not optional. We need structure in our day and we know that without structure, people go crazy. Literally. Rates of depression and anxiety go up [in situations] when there is low control and high expectations.”

Eyal was referring to a 2006 study that showed that people in jobs where they had little control of their working conditions, minimal social support and high psychological demands at work were more likely to have mental health disorders like depression and anxiety.

Humans are creatures of habit, so having a regular schedule for when we work and when we engage in leisure can help us reduce uncertainty, especially in this already uncertain time.

Laurie Santos

Compare that to our current situation, where we’re all stuck working at home, can’t spend time with friends, loved ones or colleagues, and are balancing the simultaneous demands of work, family and home school amid a pandemic. There’s a lot there we can’t control. Maintaining some kind of daily structure and sense of time helps us focus on what we can.

“I’d encourage people to find ways to replicate what they did on weekends using the current creative things we’re doing in this time. Did you do Sunday brunch every week with friends? Make some pancakes at home and meet over Zoom. Was Saturday morning the day for your big run? Then head out for a socially distanced jog,” Santos says. “The idea is to find ways to replicate the routines we had previously as much as possible to bring some normalcy back to the odd situation we find ourselves in.”

The content of your routine isn’t as important as the fact that you have one, Eyal says. The current crisis may be an opportunity to shift things around and create a schedule that accommodates your rhythms instead of an employer’s. And you also may find there are some things you like just as they are.

Carol Horne, who works for an elder-services charity in London, offered her children, aged nine and seven, the option to study from Wednesday to Sunday so that she could have more time to help them with schoolwork during her weekends. She scrapped the plan when her eldest child balked.

“She said she likes the weekend to be on Saturday and Sunday,” Horne says. “And since normality has gone out the window, I wanted to give her a tiny bit of regular routine to cling to.”