It’s been nearly a quarter of a century since I last attended a Nigeria international in Nigeria but it seems little has changed in that time – in fact, dare one say, some things might have got worse.

I was present on Tuesday night as hundreds of spectators stormed the pitch at the Moshood Abiola National Stadium in Abuja following the hosts’ World Cup exit at the hands of fierce rivals Ghana.

Nigeria requested a full-capacity crowd of 60,000 for the World Cup play-off, but the Confederation of African Football (Caf) authorised only 39,000 – owing to Covid concerns – to attend a game, ultimately overseen by Fifa, that was packed to the rafters on the night.

Officials had urged fans to attend, while Nigeria’s football federation (NFF) and sports ministry jointly gave away 20,000 free tickets, a move which may have backfired given the possibility that some of those fans may have engaged in the wanton violence.

The events raise familiar questions about security and policing at games in Africa – and the lack of serious response by governing bodies to these incidents – despite high-profile events at this year’s Africa Cup of Nations in Cameroon, including the Olembe Stadium tragedy.

My experience this week took me back to scenes that followed the Nations Cup final in 2000.

On that occasion, after Nigeria lost to Cameroon on penalties, a blizzard of stones rained down upon the pitch in Lagos – one of which left a man standing next to me pitch-side with blood streaming from his face.

When it came to leaving the stadium after that defeat, the Nigerian players used a decoy bus – fearing theirs would be attacked by their own supporters – to secure safe passage away.

Behind them, a phalanx of riot police, armed in their protective body armour and helmets, tried its best to dispel the crowds and stem any major incident, violence or possible loss of life.

Yet on Tuesday in the Nigerian capital, despite the magnitude of the opposition and game, I spotted no riot police, nor did any appear as the pitch invasion which followed the final whistle of the 1-1 draw that took Ghana through on away goals went on for at least 10 minutes.

The mob were briefly interrupted when a lone official threw a tear gas canister onto the pitch, dispersing the hordes of fans on the pitch like a shoal of fish from a falling stone, but they were soon back.

‘This is insane’

Fans overturned the Nigerian dugout, smashing up the perspex after it fell, while dozens picked up chairs as weapons – with a BBC colleague telling me he saw one fan with a knife on the pitch.

I was briefly threatened by one chair-wielding fan after gathering reaction from the hardy group of Ghana followers, who numbered around 100 or so, as they chose to cross the pitch – thankfully unharmed – to reach safety, rather than risk going outside a stadium that was dreadfully lit in many places.

“They are treating us very badly,” one Ghana fan, who says he had lived in Nigeria for over 30 years, told BBC Sport Africa.

“This is insane,” said another as he scurried forward. “This is football – it’s win, draw or lose – you need to understand what is going on.”

As the Ghanaians – many scared – stuck together in a bid for safety, security services were nowhere to be seen.

The same thing had happened when the Black Stars players had to cower and cover their heads with their arms as they sprinted to the tunnel to escape the hailstone of bottles and the charging mob behind them.

The play-off featured nine Premier League players, as well as several top-flight footballers based in Italy, Spain, France and Portugal.

Like the fans, who were also pelted with bottles, the Ghana delegation was so keen to escape the stadium they missed the compulsory post-match press conference (while Nigeria’s failure to face the media had less excuse).

Fifa investigation?

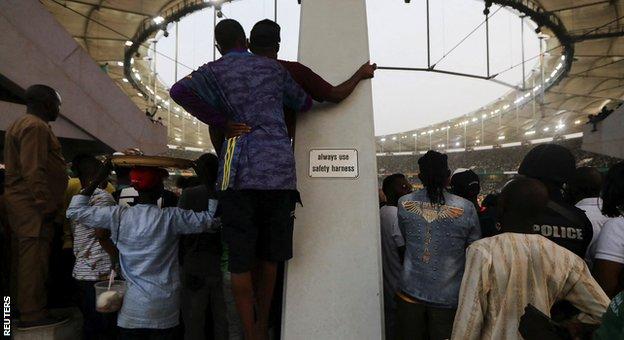

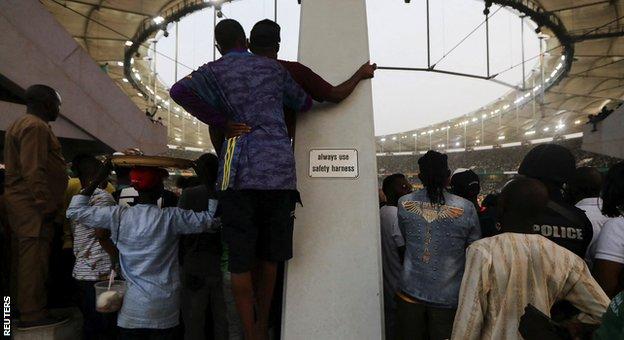

Inside the stadium, there was scant attempt by authorities to stem the invaders, quite the opposite at times.

In sections of the stadium, I saw gates keeping fans from the pitch inexplicably opened after full-time. It summed up the approach to stewarding, while policing was also near non-existent.

Even getting into the stadium itself, which I did over three hours before the 17:00 GMT kick-off, was fraught with difficulty.

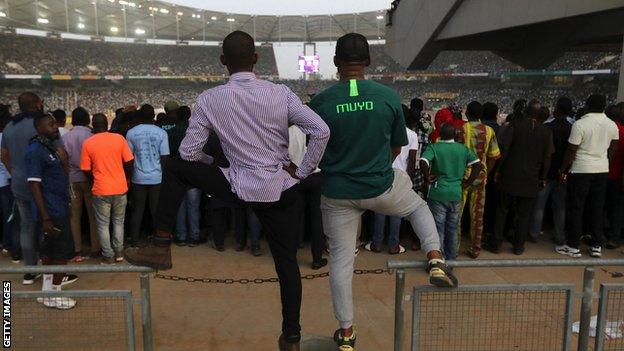

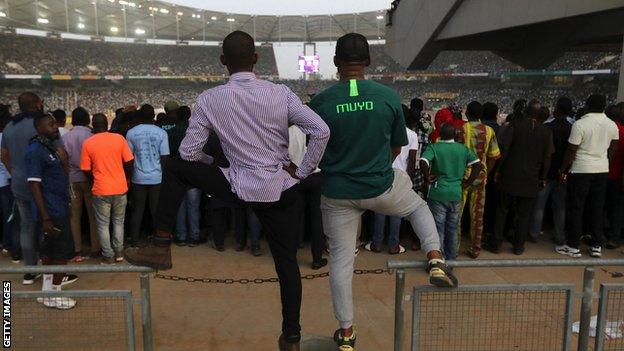

There was no order as fans pushed right up against the turnstiles to such effect that sometimes three or four people were inside a turnstile which, funnily enough, didn’t move so quickly as it repeatedly got stuck.

Amidst this entry scrum, I had a phone and wallet stolen while trying to protect my rucksack.

Questions need to be asked of Nigerian football and security authorities, Caf and Fifa too, as to how such a scene could have played out in such a showpiece event – a game under the auspices of football’s world governing body.

Was it really too much to foresee the potential for trouble following a possible Nigeria exit at the hands of their closest rivals?

And if not, where was the seemingly-invisible security presence?

It is the NFF’s responsibility to oversee the stadium security with local authorities and while Caf and Fifa may send security officers, these individuals are there to advise and oversee.

Fifa has told BBC Sport Africa it is analysing official match reports, and will then decide what disciplinary action will be taken against Nigeria, if any.

Repeat incidents

It’s the third time in just two months I’ve attended a match in Africa where policing and security has been regrettably sub-standard, with a pitch invasion after Algeria played Ivory Coast at the Nations Cup preceding the Olembe Stadium disaster in January.

In the Cameroonian capital, eight fans died following a stampede outside the stadium whose roots largely lay in local authorities’ unbelievable decision to funnel most of the supporters attending an arena built for 60,000 to one main entrance, a gate not much wider than a garage door.

Why, in 2022, are such incidents still being allowed to happen by those responsible for the safety of spectators?

To its credit, Caf has barred several countries’ international stadiums from being used owing to their unsuitability to host matches, but the issue of enforcing security at games, not to mention a safe stadium access policy, is still not right across the continent.

Regrettably, precious little tends to happen after these types of events.

It’s often a minor financial slap on the wrist, which is often dwarfed by the fines football’s governing bodies farm out for the “important” things such as breaching advertising rules.

I attended a 2010 World Cup qualifier between Senegal and The Gambia in 2008 where fans not only set fire to sections of the stadium but also smashed up the VIP areas near which the teams sheltered for their lives. The punishment? Nothing.

The same inaction over overcrowding was also present in the Abuja stadium itself, where walkways and every available inch of concrete was taken up by spectators.

This is a massive hazard yet a constant sight at so many African matches – why is it still allowed to go on?

The aftermath of Tuesday’s game overshadowed an unforgettable clash between two West African countries whose historic rivalry spreads across football, music, films and, among many other things, gleeful banter about whose famed jollof rice is better.

The ribbing is often good-natured but in the press area itself, some Nigerian journalists issued their Ghanaian counterparts, who had unwisely been celebrating as the full time whistle approached, with death threats, as the frenzied madness spread.

It’s no secret that football can whip up a storm of incredible emotions so why are authorities still either unable or, worse, unwilling to take appropriate action to stop this?