African states are increasingly acquiring Turkish drones to fight armed groups after they proved to be effective in various conflicts around the world, writes analyst Paul Melly.

As Ukraine stepped up its initial fightback against Russia’s invasion, and long before Western heavy artillery and rocket launchers started to arrive, there was one weapon that the Kyiv government could already deploy – the Bayraktar TB2 drone.

This Turkish-made weapon had already proved its effectiveness in helping Azerbaijan defeat Armenian armoured forces and snatch back extensive territory in the Nagorno-Karabakh war of 2020.

But admirers of the drone’s capabilities are not confined to eastern Europe and the Caucasus.

Recent weeks have seen a consignment of Bayraktar TB2s delivered to the West African state of Togo, which is struggling to curb the infiltration of jihadist fighters moving south from Burkina Faso.

While in May, Niger acquired half a dozen of these versatile and affordable drones for its military operations against insurgent groups in the Sahel region south of the Sahara Desert, and around Lake Chad.

Other African customers have included Ethiopia, Morocco and Tunisia, while Angola has also expressed interest.

But the first to use these potent surveillance and strike weapons on the continent may well have been the UN-recognised government in Libya – where whey were spotted as early as 2019 and may have helped Tripoli’s forces hold off eastern rebels.

For African buyers, especially poorer countries, drones provide the chance to develop significant air power without the vast cost in equipment and years of elite training required to develop a conventional air strike force of manned jets.

This is a particular attraction for states such as Niger and Togo.

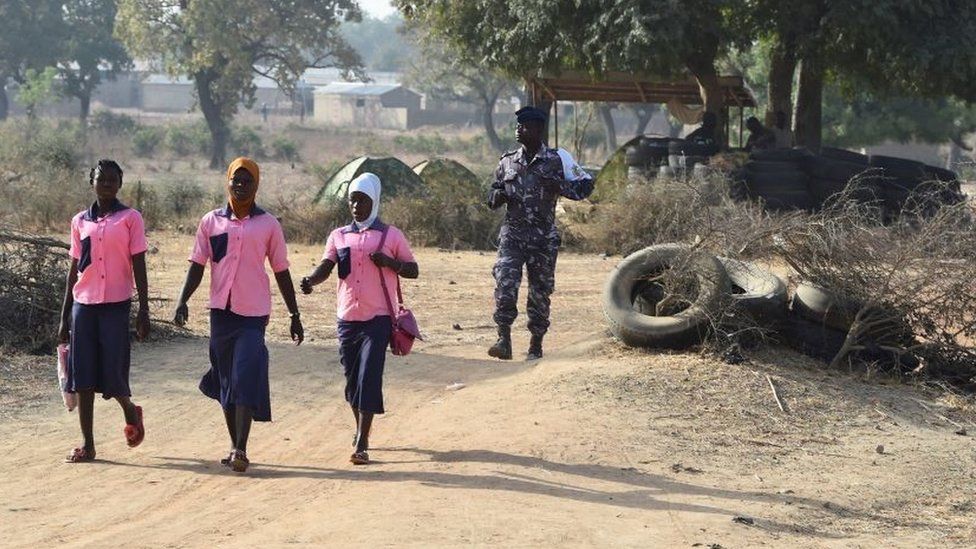

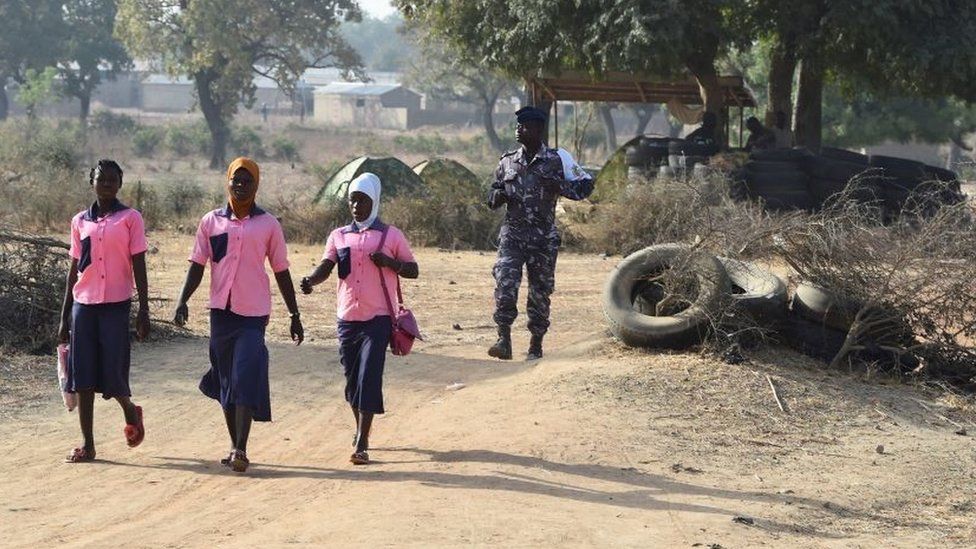

They face the complex challenge of curbing highly motivated and mobile bands of Islamist militants, camping out in the bush and moving quickly through the scrubby terrain of the Sahel by motorbike to stage ambushes and surprise attacks on isolated army and gendarmerie posts, border crossings and civilian communities.

Niger’s army has been grappling with this problem for years, fighting militants in the tri-border region, where the country meets Burkina Faso and Mali, just a few hours’ drive from the capital, Niamey.

Government troops are also engaged in an arduous campaign to protect the far south-east from attacks by Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (Iswap).

But for Togo, the direct reality of the jihadist threat is a relatively new and hugely worrying experience.

For most of the past decade the activities of the militant groups were confined to the central Sahel – Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger – and mainly in areas relatively distant from their borders with coastal countries such as Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo and Benin.

But more recently the picture has begun to change, as the armed groups extended their reach across much of Burkina Faso, and into rural areas along the border with these four states.

By late 2019 security forces were detecting signs of militant infiltration into northern Togo.

Initially the fighters were just hiding out for rest and recuperation, but the government in Lomé, like its counterparts across coastal West Africa, was already concerned that the threat could grow.

Neighbouring Ivory Coast had suffered a jihadist attack on the resort of Grand Bassam in 2016, which left 19 dead, and then attacks and clashes with security forces in the north-east in 2020.

And a local wildlife guide died when militants kidnapped two French tourists in the Pendjari national park in Benin. Two French troops were later killed in a firefight when the tourists were rescued across the border in Burkina Faso.

The first direct raid on Togo itself, at Sanloanga, came last November. Then before dawn on 11 May, dozens of militants attacked an army outpost at Kpék-pakandi, near Burkina Faso, leaving eight soldiers dead and 13 wounded.

The troops fought back, killing some assailants. The next month the government decreed a state of emergency in Savanes, Togo’s northern-most region.

But that has not been enough to deter the jihadists now operating in the frontier zone and thought to be affiliated to Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin, the main alliance of Mali-based Islamist armed groups. Two soldiers were killed in another incident in July.

President Faure Gnassingbé has toured the area in an effort to bolster morale. But some badly shaken locals have been abandoning their villages – a phenomenon already seen in other parts of the Sahel afflicted by militant violence.

The regime used to monopolising power for decades has even felt the need to invite opposition parties for talks about developing a united national strategy to cope with the militant threat.

But ultimately, direct military force will have to play a role. And that is where the Turkish drones come in, providing Togo – like Niger – with its own national aerial surveillance capacity to try to spot bands of militant fighters and, potentially, strike against them.

The use of drones is not new to the Sahel. Both France and the US have drone bases in Niger, operating in support of the government’s security strategy.

For larger powers such as Ethiopia – where the federal government has been battling the Tigray People’s Liberation Front – drones are a valuable tool for expanding overall military capacity.

But there are risks, just as with manned aircraft. By January, aid workers were reporting that drones had killed more than 300 civilians in Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict.

And the Togolese military have admitted killing seven young civilians in error, after an aircraft – whether manned or unmanned is unclear – thought they were a group of militants and launched a strike on 9-10 July.

The risks of such tragic mistakes are heightened at moments of panic about the apparent infiltration of jihadists.

For both Togo and Niger the supply partnership with Turkey is also politically useful, reducing their public reliance on close security partnerships with France, the former colonial power, about which a significant strand of domestic opinion remains uneasy.

From Ankara’s point of view there are also attractions: “drone diplomacy” and military partnership have become a significant tool in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s foreign policy outreach south of the Sahara, complementing more long-standing strengths such as the building of airports and other key infrastructure.

And within the Turkish politico-business elite there is a personal connection too.

Baykar, the manufacturer of the Bayraktar TB2 drone, is headed by two brothers – chief executive Haluk Bayraktar and his brother Selçuk, chief technology officer, who happens to be married to President Erdogan’s daughter Sümeyye.

Paul Melly is a consulting fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.