There is a wealth of psychological and biological information stored in our scent, but for some reason we choose to ignore it.

King Louis XIV of France was obsessed with fragrance. Cut flowers adorned every room in Versailles, furniture and fountains were sprayed with perfume and visitors were even doused before entering the palace. Whether it was because his personal hygiene was not up to the standards we might expect today, or he just enjoyed playing with scent, Louis understood that smell is important.

Our body odour can reveal details about our health, like the presence of diseases (cholera smells sweet and acute diabetes like rotten apples). “It can also reveal information about our diet,” says Mehmet Mahmut, an olfaction and odour psychologist at Macquarie University, Australia. “There are a couple of studies that kind of contradict, but my group found that the more meat you consume the more pleasant your BO smells.”

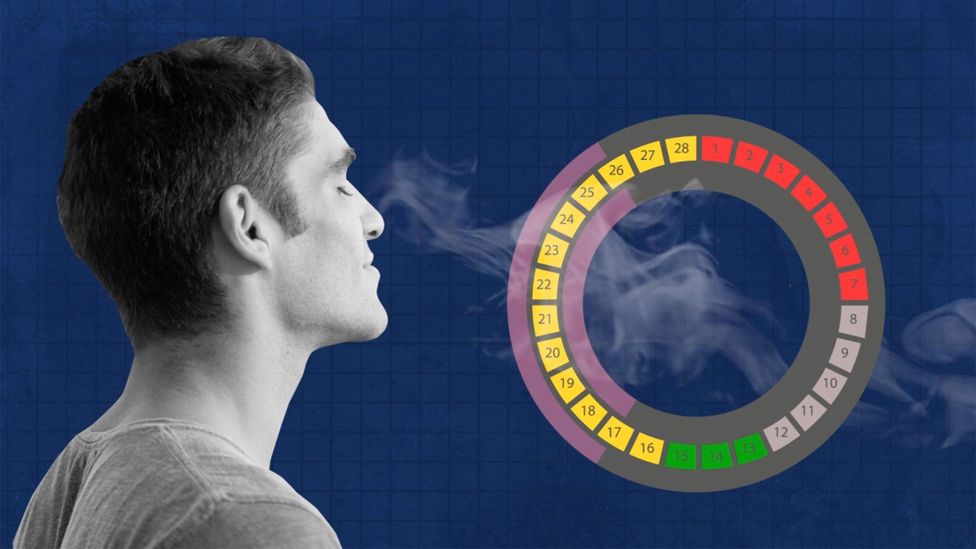

Men find women’s body odour more pleasant and attractive during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, when women are most fertile, and least pleasant and attractive during menstruation. This might have been useful for our ancient ancestors to detect good candidates for reproduction, suggest the authors of that paper. Men’s testosterone levels might improve their scent, too.

While it can change depending on our diet and health, a lot of what makes our smell unique is determined by our genetics. Our body odour is specific enough, and our sense of smell accurate enough, that people can pair the sweaty T-shirts of identical twins from a group of strangers’ T-shirts. Identical twin body odour is so similar that matchers in this experiment even mistook duplicate T-shirts from the same individual as two twin T-shirts.

“This is important because it shows that genes influence how we smell,” says Agnieszka Sorokowska, a psychologist and expert in human olfaction at the University of Wroclaw, Poland, “so, we might be able to detect genetic information about other people by smelling them.”

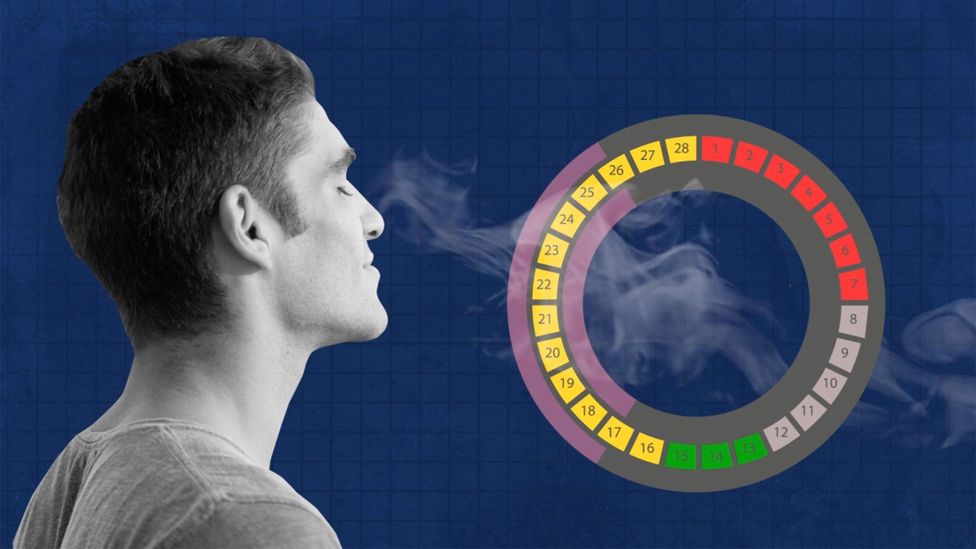

Collectively we spend billions of dollars trying to change or disguise our natural body odour with perfumes and fragrances (Credit: Michal Bialozej)

We choose cosmetics that match our genetically-determined odour preferences. Sorokowska and her colleagues have shown that it is possible to make assessments of someone’s personality based on their choice of fragrances. It suggests that guests of Louis XIV might have been able to pick up a thing or two about the king by sniffing the air upon arrival.

All of this information is in our BO, but is it useful to us?

In one study, women were given T-shirts worn by random men and asked to rank them by how pleasant they were. Their order of preference followed the same pattern as something called Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) dissimilarity.

HLA is a group of proteins that helps our immune system to identify cells that belong to us and cells that are from something or someone else – and are therefore potential pathogens. The gene complex that encodes for HLA, called MHC, also encodes for some other proteins used in our immune response, and is useful as a shortcut for scientists to see what kind of protections our immune system can offer.

If you have a partner who is genetically dissimilar in immune profile, then your children will have a better resistance to pathogens – Agnieszka Sorokowska

Your HLA profile is very likely to be different to everyone else you meet – though some people, like your close relatives, will be more similar to you than others. From a genetic point of view, it is an advantage to have a child with someone who has a dissimilar HLA profile. “If you have a partner who is genetically dissimilar in BO and immune profile, then your children will have a better resistance to pathogens,” says Sorokowska.

These women put the T-shirts worn by men with the most dissimilar HLA profile first and last the most similar. So they were able to identify the men, and preferred the men, with the best match in terms of immune system genetics. They didn’t know that was what they were doing, of course – it was subconscious.

The specific mechanism that causes HLA-dissimilarity to result in a better-smelling BO is not known, says Sorokowska. “But it is thought that HLA results in the production of certain substances that are digested by our skin bacteria that produce a certain odour.”

Do humans use genetic information hidden in body odour to choose their partners? It would seem not. In a study of almost 3,700 married couples, the likelihood of people ending up with a HLA-dissimilar partner was no different to chance. We might have a preference for certain smells, and there might be a genetic reason for that, but we don’t act upon smells when choosing who we marry.

“But even though HLA does not influence choices, it influences sexual wellbeing,” says Sorokowska. People with congenital anosmia (the loss of their sense of smell) have poorer relationship outcomes, suggests Mahmut in a study with Ilona Croy at the University of Dresden, Germany.

Many of the experiments on body odour ask women to rank the t-shirts worn by men, and sometimes even their own husbands (Credit: Michal Bialozej)

Couples who had high HLA-dissimilarity – which presumably happened by chance – had the highest levels of sexual satisfaction and the highest levels of desire to have children.

This link was more strongly seen in women. Women partnered with HLA-similar men reported more sexual dissatisfaction and lower desire to have children. Though when evidence from multiple studies is taken into account, the effect might not be conclusive.

To evolutionary biologists the emphasis on female choice makes sense. In nature, females tend to choose males, as it is the mother who invests the most in raising children and therefore has the most to lose by mating with a genetically inferior male. The female must be discerning in her choice, so looks for clues as to a male’s quality. This is why males are often colourful, perform dances, sing songs or offer gifts in nature – they have to prove their genetic quality.

The link between BO preference and genes spurred a fashion for T-shirt speed-dating and even “mail odour” services. But the evidence to support the idea we can make good dating decisions based on smell is unclear. We might say we prefer something, but in practice it would appear we do not make choices based on that preference. Why not?

One reason might be that real-life scenarios are too complex to use scent information accurately. Our other senses can distort the information we take in from smell. Based on body odour alone, we can make accurate assessments of other people’s neuroticism. But when shown a photo of that person alongside a sample of their BO “they got confused”, becoming less accurate, says Sorokowska. “And we are not able to rate neuroticism from faces alone.” She says that BO is more accurate for judging neuroticism, but faces are easier, and often we just do what is easiest.

We spent tens of thousands of years disguising what we smell like – Mehmet Mahmut

In another study, married women brought in their husbands’ T-shirts and single women brought in a platonic friend’s T-shirt and these were mixed up with more T-shirts from random men.

“Did partnered women end up with someone whose BO they preferred to others?” says Mahmut. “Not necessarily. There was no overwhelming evidence they put their partner at number one.” In this case, the women had not chosen a husband who had the BO that smelled best to them.

In a separate study by Mahmut, strangers’ BO also smelled stronger than married men’s BO. He speculates that this might be because “there’s some evidence of a correlation between high testosterone levels and stronger BO. We know there is an association between a reduction in testosterone and getting older, which might be due to the things going on in a married man’s life as he gets over 40 – prioritising children and things like that. Men who are in relationships, and more so those that have had children, have lower testosterone.

Men can find women’s body odour more attractive at key points in their menstrual cycle (Credit: Michal Bialozej)

So, we know that we give off information about our reproductive quality in our BO, and we know that we can detect it, but we don’t act on it. Should we?

“If your sole interest is finding a partner with good genes, then perhaps you should pay attention to their smell,” says Sorokowska. “But for most people that is not the most important thing, and most people don’t do it.”

Mahmut agrees: “The usefulness of scent has somewhat decreased. We spent tens of thousands of years disguising what we smell like.”

* William Park is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets at @williamhpark

This article is part of Laws of Attraction, a series co-produced by BBC Future and BBC Reel that explores the roles our senses play in how much we like each other. The articles and films were written by William Park. The films were animated by Michal Bialozej and produced by Dan John